- Home

- Varun Gwalani

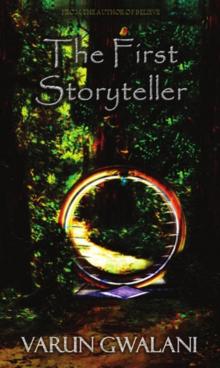

The First Storyteller

The First Storyteller Read online

The

First

Storyteller

Varun Gwalani

ISBN 978-93-52016-00-6

MRP 225

Copyright © Varun Gwalani, 2016

First published in India 2016 by Frog Books

An imprint of Leadstart Publishing Pvt Ltd

1 Level, Trade Centre

Bandra Kurla Complex

Bandra (East) Mumbai 400 051 India

Telephone: +91-22-40700804

Fax: +91-22-40700800

Email: [email protected]

www.leadstartcorp.com / www.frogbooks.net

Sales Office:

Unit No.25/26, Building No.A/1,

Near Wadala RTO,

Wadala (East), Mumbai – 400037 India Phone: +91 22 24046887

US Office:

Axis Corp, 7845 E Oakbrook Circle Madison,

WI 53717 USA

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Disclaimer: The Views expressed in this book are those of the Author and do not pertain to be held by the Publisher.

Editor: Sanjeev Mathur

Cover: Vibhawari Jammi

Layouts: Logiciels Info Solutions Pvt. Ltd.

Typeset in Palatino Linotype

Printed at Repro

Dedication

This book is a tribute to all the storytellers and their

incredible stories without which I would not have survived

the dark years.

About the Author

Varun Gwalani is a young author living in Mumbai. A TEDx speaker, he has spoken about his struggle with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and the impact it has had on his writing. He is an advocate of better mental health awareness, gender equality, and alternative styles and themes of writing in India. He has previously published a novel, Believe, which represented the setting of a fictional world without any indigenous mythological elements. (This book is not a sequel to Believe). He is happy to answer fan questions and receive feedback, and can be emailed at [email protected]

Acknowledgments

There is much to be said about the loneliness of writing, but especially of writing this particular book, but I would still like to extend my gratitude to:

My family, for not throwing the book at me while I continued to pursue my mad quest of writing.

Gigi. Even though the singing of the birds seems far right now, I have faith that one day they will come back and lift you up with their song.

Aayush and Nidhi. Stories are just words screamed into the wind until there is someone on the other end to listen to them.

Bindiya, for the aftermath. And the strength.

And to you, dear reader, if you have listened to all my stories. Don’t forget to keep walking. The end will come when it has to, whether you sit and wait for it, or whether you run with the wind in your hair and a light in your eyes.

1

The Last Storyteller

What makes the dawn beautiful? There is an old story, now known almost exclusively to me, that proclaimed that the coming of dawn heralded a new day. A red blooming streak rose out of the ocean, driving away the darkest hours before it; creating a world full of possibilities, resurrecting the idea of hope through its own resurrection.

If you were one to believe legends, then there is no hope in the land that does not die- the land of the eternal dawn.

I looked out at the unchanging undulating dawn, trapped midway ‘twixt heaven and earth; an aged seductress that had long lost the ability to tempt fickle humanity; but still kept the eternally youthful world trapped in her clutches, in that one shared desperate hope of all those who believe themselves to be alone, but do not wish to be. The lonely dawn wanted someone, something to stand up, throw out their hands and scream, “I understand! You are fleeting! You are not forever.”

I did not throw my arms out. I did not scream. How could anything be beautiful when you saw nothing else?

I stood at the very edge of the cliff, jagged, deadly, benevolent rocks; ready to end life at a moment’s notice, no questions asked. Questions, they said, are for the living, not the dying. The question was now: Was I really living? Did anything I do make me worthy of death? Every time I put my head down to sleep, my head was on a chopping block; mind separating from body to sleep, and reattaching every time I woke up. What was the use of bloody death if life was less than a revolution?

I looked down at the rocks once more and considered. Monotony was deadly enough poison; it did not require a skewer of meat. I looked away from death, as I often did; with the simple continued resolution that when I had done enough to make me worthy of death, I would embrace it.

Enough standing around philosophising. I turned my back to the dawn, resolving to establish a more conventional narrative for now.

The Coast extended as far as the eye could see in either direction. Cliffs and sharp rocks prevented the people of the Coast from accessing the sea; not that they would want to. If all the myriad communities up and down the Coast had one thing in common, it was that they were all the same. They stuck to a heavily- regulated schedule, almost every breath of their short lives planned out.

On the other side of the villages was the vast, infinite Forest. Nobody could know where it ended, and nobody was sure if it ended at all. It was the land of mystery, lore and legend and I had always been drawn to it, as I was being drawn to it now.

I would say that I walked towards the Forest quietly, but nobody noticed me anyway. I would say I was a ghost, but the idea of ghosts seemed more real than the idea of me. I would say I was invisible, but I was not that lucky.

All around me as I walked, people milled about, dust scattering about in the wind aimlessly, until to dust they would return, no better or different from when they had started. A tiny sound, louder than the hustle and bustle around me, seemed to fill the air (I could not tell if it really did anymore) and all activity ceased. I kept walking.

I stopped when I reached the edge of the Forest, and there stood the source of the sound, the ruler of this land: Skiros. Skiros was a large, partially hollow metal circle supported by a specially crafted stand. It was larger than you would have expected from a distance, and bigger on the inside, where sixty small metal ridges lined the outer rim at uniform intervals. There was an aura of omniscience and power among it, as if it could encompass all time within its bounds, which, of course, it did.

The liquid which created the universe originated at the topmost ridge. A single drop passed down from the top, slowly down the rim, until it reached the next ridge, and so on. It always took to the count of sixty to move from one ridge to another. Sixty seconds, as we called it. Sixty seconds to a minute. Sixty minutes to an hour. There were no days here, because for there to be a day, there has to be a night. It was twenty-four hours to a dawn. Old systems adapted for new, as it has always been.

Etched into the top of Skiros was a curving snake, its mouth open wide. The legend went that the liquid, which was called Snai, had festered in the snake’s mouth, one day forming the Universe, and escaping the mouth of the snake. It was said that the snake would once again consume the universe, and that would be the end of all time. It was painfully clear to me what the Snai was, though nobody acknowledged it: Snake venom, a slow poison.

The blue Snai reached the next ridge and that tiny sound filled the air again. There was movement in the village, and

all the villages like it up and down the Coast. We lived our lives according to Skiros, according to where that one tiny drop was. Every ridge had a unique sound, and the travelling from ridge to ridge even had its own sound. Activities were planned according to where the Snai was moving, and I don’t think that we even really heard the sound anymore. The poison was in our veins now, the change in activity was almost instantaneous, and anyone on the Coast could tell you the time down to the second. I privately called the movement of this drop the slithering of the snake.

The snake slithered now. There was a shuffle of feet as the announcement for preparation of dinner was made without a word. My face had lost the will to twist in distaste. I turned around but didn’t head for my hut. Instead, I moved towards the home of my mentor, the Storyteller. His hut was closer to the Forest than the others, as set apart from the rest of the village as he was.

I reached his hut and knocked on the door. There was no response, only a strange gurgling. I pushed the door open and the Storyteller lay on the bed, his face flush, and his eyes wide. I rushed to his side as he turned to me and smiled weakly.

“Hello, my child,” he whispered, his voice cracking. I clutched his hand. It was burning hot. He was dying.

“Please, please. What happened? What can I do to help?” I muttered desperately, rubbing his hand as if to ease out the wrinkles in the paper-thin skin. The very hands that had helped me to write and trace out words on the last forbidden scraps of paper to create new life could not now be lifeless.

“You cannot do anything to help, and you should not do anything,” he whispered, his singularly kind voice breaking my heart as it always did. “You know that extending a story after its time only bores the listener. Better to go out with someone mourning you rather than everyone waiting for you to die.”

“Oh, please, stop,” I exhorted, tears streaming down my cheeks. “No one here will mourn you. You know that. These ‘people’...,” I spat the word out, “do not value you. They never have.” “You will. Changing one life is enough for me.” “Please, no.” On my knees, I begged him. “I can call the doctor. We can still save you.” “I’ve done all I can, my child.”

“No, you’ve not. The stories are running out. Nobody listens. I...I need you. Please don’t go. Please, please.” He looked me in the eye, squeezed my hand with surprising strength and his eyes shone with the last blaze of a fire that had long been dying. He said, “All stories must end. You must decide what to do after, and I’ve always known that you will make the right decision.”

Then, he rolled over, his eyes turned towards his final destination, and his hand went limp in mine. I squeezed it harder, in the hope that it would revive him, but nothing changed. He was still dead.

The snake slithered, signalling that it was time to eat. My body started moving without instruction. I did not cry anymore, I did not say a word. I dropped his hand and left the hut, closing the door behind me. Before I knew it, I was sitting at the dining table at my hut. My emotions were in a swirl, and I was furious for having come back here.

The woman who had expelled me from her body long ago and the man who had assisted in that ignoble venture sat at the table. These people, who I referred to as my parents for the sake of convenience, were glaring at me, and I glared right back.

“Don’t give me those eyes,” my mother growled. “Where were you? You weren’t here to help with the

food, again. And you’re late to eat.”

“So what if I am?” I shot back, raring for a fight.

“So what?” My father snapped. “You’re not on schedule! You keep thinking that you’re better than the rest of us, and that you can just flaunt the rules whenever you want! That’s unacceptable.”

“No, what’s unacceptable is the inability for you and everyone in this goddamned place to think outside the circle! You’re so obsessed with rules that-”

“Here we go again!” My mother roared, standing. “Once more, we have you defying our traditions and rules. And for what? Make-believe! Literally abandoning our values for lies!”

“You’re not even worth being called a masquerade because even masks need some substance to latch onto.” I stood up, my voice full for scorn.

“Nobody understands half the words you say,” said my father, finally standing. His eyes narrowed. “You’ve been spending time with the old man again, haven’t you?” “The old man is dead,” I said, horrified at the ease at which the words slipped out, the reality of his death slipping effortlessly into the deaths I had imagined for so long, until I no long felt either.

That gave them pause, but only for a second. “At least now that unhealthy relationship you had with him is at an end,” my father remarked almost nonchalantly, but I could detect the venom underneath.

My mother was lost in thought for a few seconds before she said, “The place is going to stink for a while. The time for funerals was yesterday, now we’re going to have to wait. It’s a good thing that his hut is so far away.”

My capacity for amazement and horror was at an end, it seemed. When the man said, “Well, at least, you’ll consider giving up that ludicrous hobby of yours and letting someone else waste their time with it,” I simply turned around and walked out.

The snake slithered. It was leisure time, and that meant one of several available activities. One of them was listening to stories.

I was stomping my way to Skiros when I bumped into someone from a group of people going the other way. The person I had bumped into looked at my angry demeanour, raring for a challenge, and laughed outright. All the others noticed, and started laughing too.

There were both males and females in the group, all of them well-built from working hard in the fields and doing chores while I had been scrawny and diminutive for most of my life. They were all my age, and all very familiar with me.

“So, I’m guessing nobody’s coming to listen to stories then?” They all laughed harder now. They had found a long time ago, that engaging me in conversation often left them frustrated and confused, so they decided instead to simply laugh in my face. It took me a long time to realize that these people who were once the closest things I had to friends, some of whom I had even loved, genuinely found everything I said as amusing as the monkey who slipped on his own banana peel.

They turned around and walked away towards the prescribed physical activities, still laughing, while I stared at the bodies that I run my hand over; and the hands that had attacked my body.

The snake slithered, and my body started walking away from the mindless wrestling matches while my mind wrestled with the matches that had been struck, my soul refusing to let itself become kindling.

I reached the mound set into the ground near Skiros. There had been a time, the stories of which, ironically, only I knew; when this mound had been at the centre of the village. The community would gather and listen to wondrous tales, lessons that both entertained and educated. Now, nobody did. The mound had been pushed to the very edge of the village, where anyone who cared to listen could literally see time passing by; a passage, mind, which they instinctively knew.

The elder, who was in charge of supervising the storytelling, came and stood in his usual spot. There always had to be an elder present at storytelling, to ensure that nothing forbidden or untoward was spoken of, a definition which they themselves made, until it was impossible to speak of anything new, anything worthwhile. Nothing could defy tradition. For example, storytelling suddenly could be avoided if one chose to indulge in another activity, like a sport. This suddenly became a traditional part of a culture which had never had that in its tradition. It was easy to change history when you suppressed those who could correct that history.

No one else was there at the mound. The elder merely looked at Skiros, not even at me. The worst part about this elder was that he had no capacity for hatred or annoyance. He was never bored. He had no opinion about me or my stories or any of it. He listened to me studiously, almost attentive, but his eyes were

neither glazed over nor intense. He simply absorbed my words, and they shot right through him without reaction until he arbitrarily decided that something I had said was inappropriate.

The snake was about to slither. As soon as it did, I would have to start regardless of whether anyone was there. Talking into emptiness was not an uncommon feeling for me.

The snake slithered, the elder looked at me, and the sound of hurried footsteps was heard. A little girl rushed towards me and stopped near the mound, panting.

“I’m here on time,” she said breathlessly, looking up at me. She was someone who still listened to me as much as she could. She was a sickly girl, her face burned red, like the dawn. It had been that way since she was a child, and she had not been treated well for it. Difference was never a good thing here.

I smiled and nodded. I stood up on the mound. And froze.

I had no story to tell.

I had told all of the ones I knew, even repeated them a few times, until they had all begun to sound the same. I knew more, but I was not allowed to tell them. But I could not disappoint the girl looking at me with wide eyes, waiting. The elder glared because I had not begun on time.

“Today,” I said, all my thoughts coming together to crystallize in a beautiful moment, “I’m going to tell you about the First Storyteller.”

The elder’s eyes narrowed, but he did not comment because I had not said anything dangerous, yet.

“A long time ago, in a different land where the sun still moved and humans were just being born; there walked a woman with two children.” The elder almost moved to silence me, but the fact that I was talking of a different land bought me reprieve. “The woman was the first woman to give birth in that barren land. That day, when they were walking, the children saw several young couples walking hand-in-hand and the boy stopped.

‘“Why don’t we have a daddy, mama? You ne’er tell us,’ he said.

The First Storyteller

The First Storyteller